On MLB Opening Day in 2001, a young, spindly Japanese sensation set foot into a major league batter’s box in Seattle. A heralded prospect from Japan’s Pacific League, the player now known simply as Ichiro was a mystery. He was trying to become the first successful everyday player from Japan in Major League Baseball. He hit a bouncing ball just past Oakland pitcher T.J. Matthews, up the middle for a routine single.

In his first ever plate appearance, on the first pitch he saw, baseball’s newest Japanese phenomenon connected on a bouncing base hit through the right side of the infield in Oakland. In his first start on the mound, he logged six innings while giving up three hits, earning his first win. At 23, Shohei Ohtani is baseball’s great white whale. A player so perfect, so elusive, that Babe Ruth was the last to do what he’s attempting.

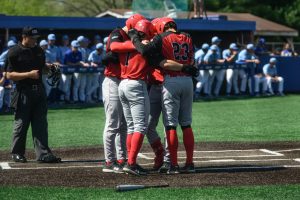

There’s something to be said about trying to accomplish something no one believes you can do. It’s interesting, it’s exciting, and it’s a struggle. There’s nobility in pursuit. From Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier to Pat Vinditte pitching with both hands, there’s something special about breaking through with something new. If there’s one thing about firsts, especially in sports, it’s that people show up. They come in droves to witness greatness, and they go home in awe. This year, they’ve hopped in their cars decked out in scarlet jerseys with rally monkeys in hand.

When I was six years old, my dad went on a business trip to Seattle and brought me back a #51 Ichiro T-shirt. That thing was my prized possession. I slept in that shirt so many times that the heat-transfer vinyl worn out, and you could hardly read the number on the back. I was Ichiro for Halloween. I practiced his batting stance and tried to hit left-handed. When we went to Texas Rangers games, we tried to pick the games against the Mariners so we could watch Ichiro.

There’s something about Japanese baseball players that intrigues me, and evidently, a whole lot of people. Maybe it’s their focus or their attention to detail. Ichiro carried his bat to the ballpark in a humidor every day and swung the bat for ten minutes every night before going to sleep. Before games, he eats two pieces of toast, the first toasted for precisely two minutes, thirty seconds, the second piece for one minute, thirty seconds, to account for leftover heat in the toaster.

Maybe it’s the way they play baseball with respect. Ohtani touches the brim of his cap and bows ever so slightly every time the umpire throws him a new ball. He repeatedly thanks his teammates for making plays on defense until they acknowledge him. It’s a posture and an attitude of honor that Americans are never taught, yet it’s unquestioned. We respect it.

There’s the challenge of coming to a new country, speaking a new language and the mystery of whether or not their dominance in the Japanese leagues can transfer to America. For every Hideki Matsui, for every Ichiro, there are 10 Kazuo Fukumori’s.

Ichiro and Ohtani could not be more different players in stature. Ohtani stands at six feet four inches with broad shoulders. For every game Ohtani pitches, he hits for three. Ichiro has maintained his slim, cut, five-foot nine-inch figure, his sleek, silky-smooth thrust of a swing and an outfield arm with laser-like accuracy. But their mindset is eerily similar, from the way they calmly interact with the media, to their Bushido mentality and humble personality. Their goals large, yet believably attainable.

Ichiro has gone on to record more professional hits than any player ever, including over 3,086 in Major League Baseball. He set the record for hits in a single season (262), and has continued to extend his career into his 18th season.

As for Ohtani, there’s no saying how far he’ll go, but I hope that young kids all over get to experience Ohtani’s greatness, like I did with Ichiro. Ohtani might just be the best thing to happen to baseball in our lifetimes. For now, we should all embrace the mania, and respect the struggle and just wait to see how the ball bounces.