The Scout reports that the day was a Sunday. April 29, 1990, to be exact. About a dozen members of the Ku Klux Klan gathered on the corner of Elmwood and Main Street in Peoria.

Across the street, near Harper and Burgess Hall, a hundred or so students gathered to protest the Klan’s appearance. There was no physical contact. There was virtually no exchanging of words between the two sides. On the front cover photo of the May 4 edition of The Scout, a Black student tries to engage with the group, though it’s not clear if he was successful.

“And then the police arrived and then after that I think it pretty much dispersed. No violence broke out or anything like that,” James Fitzpatrick, a 1991 Bradley graduate, said reflecting 30 years later. “I think that [at that] time, I was realizing ‘Wow, I’m actually looking at the Hoods.’”

The answer for why the Klansmen–some of them reported by The Scout to have come as far away as Chicago–showed up near Bradley’s campus that spring day is not a short one.

To understand that moment is to understand the entire story of what took place on the Hilltop in the spring of 1990.

The Call to Act

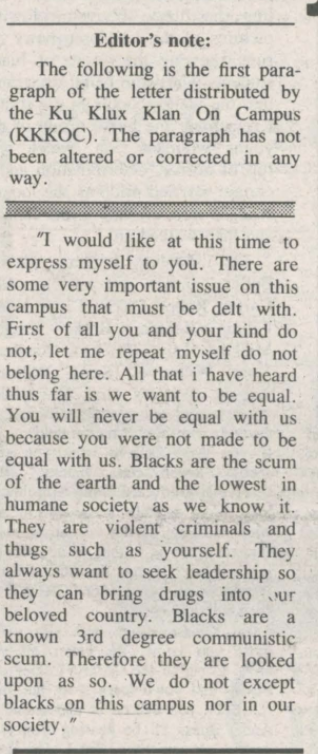

At the beginning of that semester, two Bradley student-led groups emerged and started to gauge interest from the student body. One was the Ku Klux Klan On Campus (KKKOC) group, which distributed a letter on campus promoting white supremacy. The letter, according to the Feb. 9, 1990 edition of The Scout, called Black people “the scum of the earth” and “violent criminals and thugs.”

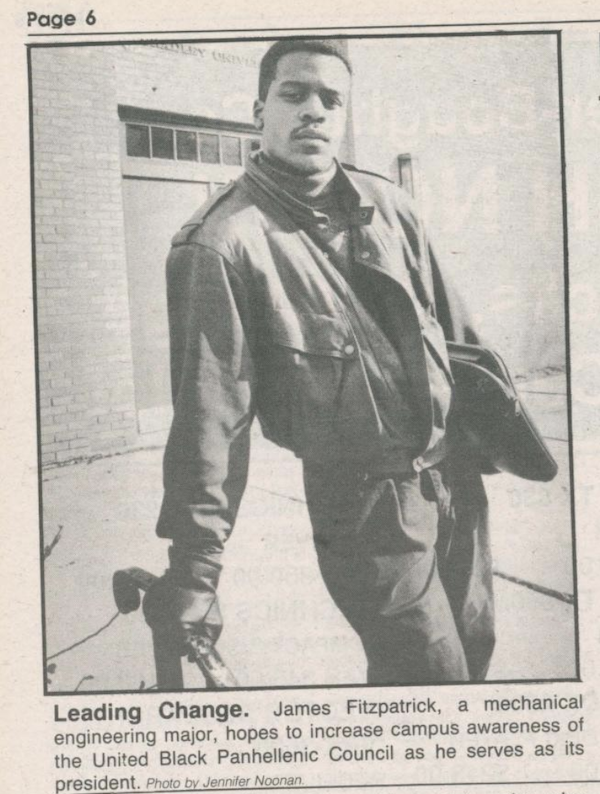

This letter was one of the many racist pamphlets that were distributed that semester, according to Fitzpatrick, who was 21 years old at the time and a mechanical engineering major. Fitzpatrick was also the president of the United Black Panhellenic Council at the time.

According to The Scout, little was known about this group.

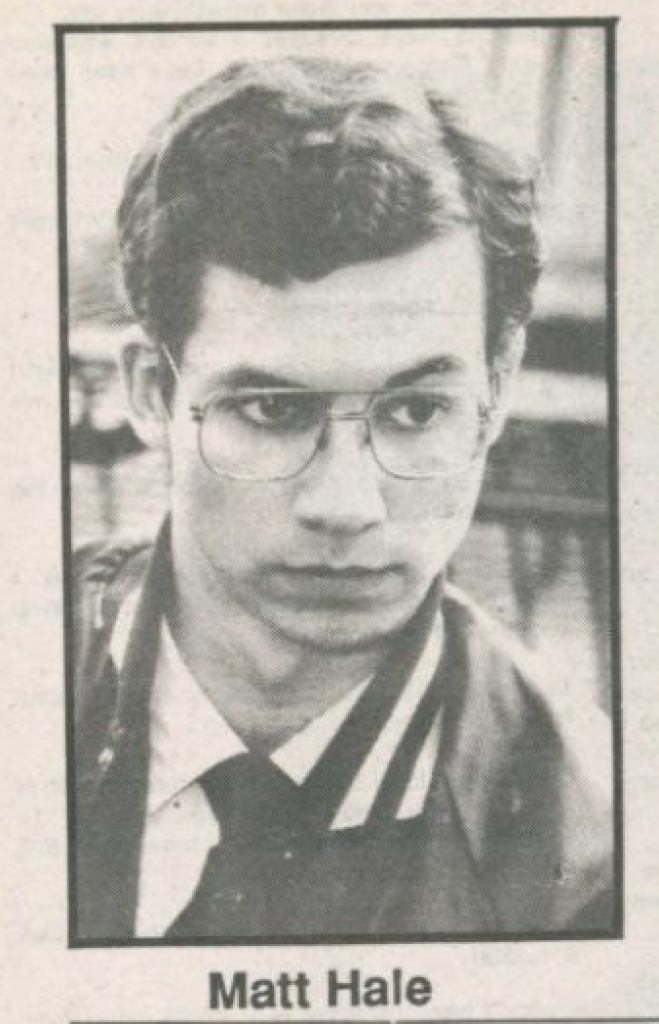

The other group was the American White Supremacy Party, and its founding member was then-freshman Matt Hale. He ran the organization off-campus and had started to seek out potential student interest. According to The Scout, Hale claimed he did not have a connection with KKKOC.

Fitzpatrick said the presence of the two organizations started to worry students and that Black students got together throughout campus for a meeting to decide what to do.

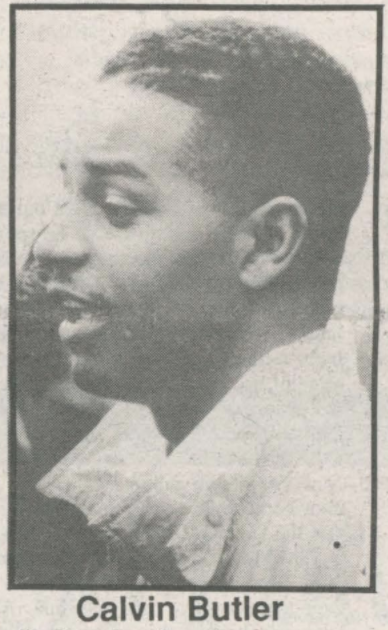

Out of the discussion came the idea to form a group that established itself as the Bradley Minority Coalition on Feb. 6, 1990. Fitzpatrick, along with fellow student Robert Davis, were named co-chairmen of the group. Calvin Butler, a 1991 graduate who now serves on the Bradley Board of Trustees, was named the spokesperson for the coalition.

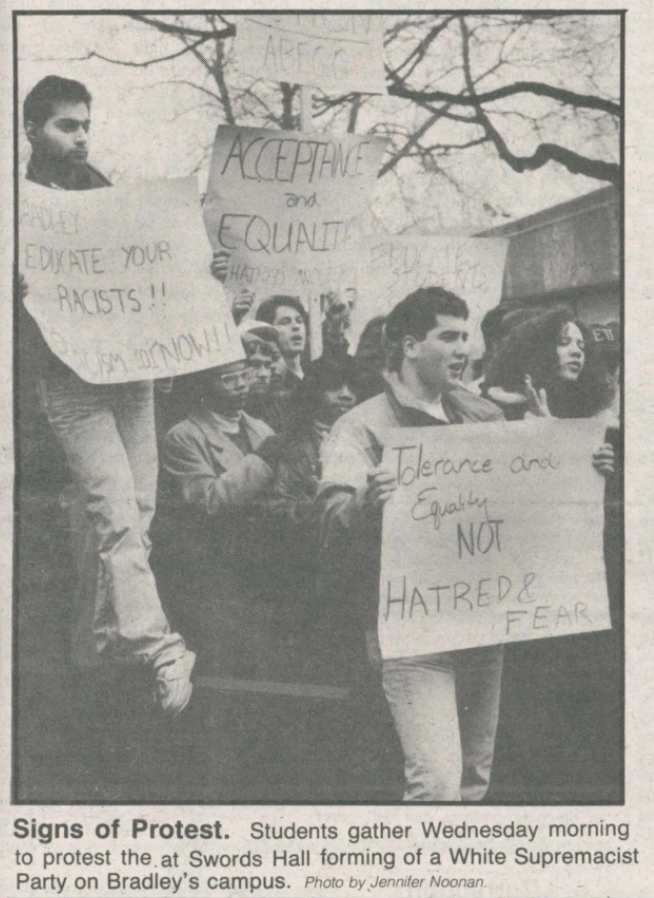

The following morning, the group gathered in front of the student center with hundreds of students—perhaps nearly a thousand according to Butler—who marched toward Swords Hall, where the Coalition had set up a meeting between then university President Martin Abegg and then Provost Kal Goldberg.

“It was really always about: [what were] we saying about us as a university that a student or a group of students felt it was okay to post flyers on campus to form a white supremacy organization,” Butler said, reflecting on the group’s talking points. “What was it saying about the administration environment that was created to think that would be okay?”

To Butler, the flyers and the notion to start a white supremacy group was only a catalyst for approaching larger problems. The formation of the Minority Coalition filled a gap and a need to address race and diversity-related issues on campus.

Some of the first demands the group pitched were to have students take mandatory race-relations courses. Through public forums held on campus in that first week of February, those calls expanded: increased recruitment of minority faculty and students; a university divestment from South Africa in protest to apartheid (in the next week Nelson Mandela would be released after serving 27 years in prison; he would go on to become the first president of South Africa in 1994); and renovations to the Garrett Center, which did not have air conditioning at the time.

Butler and Fitzpatrick both said that the Garrett Center was not considered a point of priority to the university.

“Because [Black Greek organizations] were not large enough to have houses, the Garrett Center was our place,” Fitzpatrick said. “That was the only place we really had to have our functions … That was our spot and it was the smallest building on the campus and it seemed like it was underappreciated. It seemed like the administration only kept it there to pacify us but did nothing with it.”

A diplomatic conversation

According to the Feb. 16, 1990 edition of The Scout, following the first week of protests and meetings, the Minority Coalition continued to meet with Abegg, Goldberg and associate provost of student affairs Alan Galsky. Galsky, according to Butler, was the main point of contact between the student body and administration and worked closely with Butler.

But looking back, Fitzpatrick and Butler both said the administration was not completely indulged in the conversation.

“I think for a minute they understood … but their biggest wish [was] that it go away,” Butler said.

In order to make sure the focus on these conversations did not waver, the Coalition applied pressure on the administration by attracting media attention. That week a student anti-racism protest was held outside the Civic Center during the Homecoming basketball game. Butler, in an act to make a statement that he was not a hypocrite and still focused on obtaining the students’ demands, refused the Homecoming King crown.

“That was another cycle of media attention on why these issues were important to us,” Butler said. “And those were the type of things we felt we had to do, otherwise it would have been one of those things that would have been discussed and gone.”

During that same week, Matt Hale was placed on disciplinary probation for “posting the flyers without approval and for threatening the educational process,” according to The Scout, until the next school year. It put him at risk for expulsion should he act against any school policy.

Looking back, Butler said he expected a more severe punishment but has come to understand what the university’s thought process was.

“It is an institution of higher learning and all views are welcomed, you just don’t have to fund them and nor do they have to use your facilities to do it,” Butler said. “But were we disappointed that he wasn’t kicked out of school? Absolutely.”

Meanwhile, Hale was holding meetings for his American White Supremacy Party group at his home in East Peoria.

Niels Sorrells was The Scout reporter covering Hale during that time. Sorrells said he went to report on one of Hale’s first meetings and recalled a few other media outlets attended. He also recalled that there was no one of college-age attending the meeting.

“We left because there was nothing to be done,” Sorrells said. “He wasn’t going to let us into his meeting. It was clear that it was just him. He was the only Bradley University representative there.”

Hale continued to attend Bradley after the spring 1990 semester and eventually graduated from the university. During the following years, he would continue to write letters pushing his agenda that were printed in The Scout’s “Letters to the Editor.” Sorrells said the paper let the letters be printed under the similar mindset that Butler iterated: The university was grounds for free thought, even if there was a large rebuke against the letters’ contents. Sorrells added that during some editions, it was the only letter sent in.

“If no one else voices their opinion and this is the only opinion being thrown out there, what do you do?” Sorrells said.

During the 1990 semester, however, there were conversations taking place beyond the “Letters to the Editor” section. In the coming weeks of the semester, open forums were hosted on campus and among the Black Greek organizations to assess how the campus felt.

“What we should encourage is debate,” Butler said. “I may disagree with you, but you have the right to think what you want as long as it doesn’t infringe on my ability to live and learn.”

Campus of Emotions

Throughout the semester, the atmosphere was becoming tense on the Hilltop.

Butler said the presence of Hale’s ideologies was creating a toxic environment and made students uncomfortable and scared. In an early forum, he recalled students crying.

Despite a massive showing of support, Fitzpatrick said there were people who expressed that the protesting should be dropped.

Others had more explicit threats. Butler said he received hate mail and death threats from as far as Boston. One article from the Feb. 9 edition of The Scout reported a bomb threat was called into a Jewish fraternity on the day of the first rally.

As the semester progressed, Butler said he realized the presence of Hale was not just limited to affecting Black students. Heading into late April, the group decided to make a name change to the Multicultural Awareness Coalition to account for other groups as well.

“Everybody was coming together,” Butler said. “That’s why it was so pivotal at that time, because it rallied us around it. Because before that, we were all coexisting as college students … and then all of a sudden your world was shaken up.”

This story is part two of this series

Who They Became

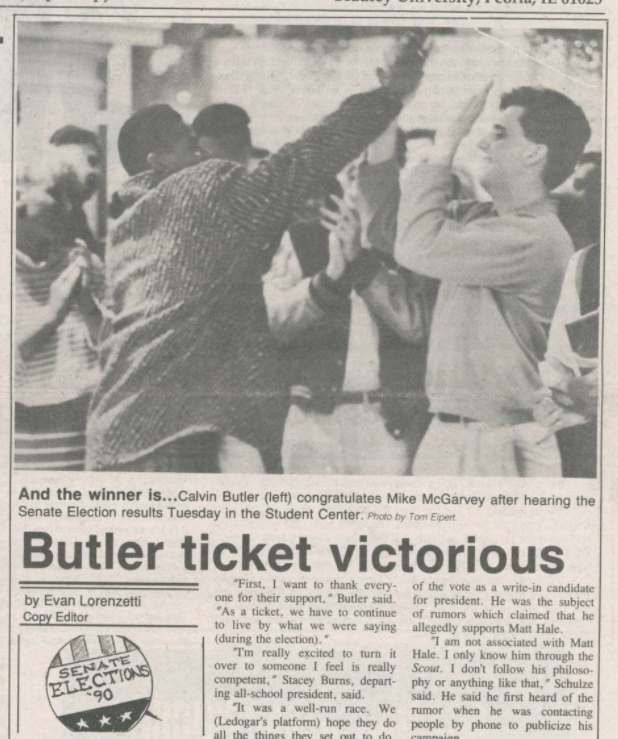

In the second week of April, student government elections were held on campus, with Calvin Butler running on a ticket as a candidate for president. James Fitzpatrick remembered the election as a time when the campus came together to establish a consensus on how to choose their student leadership for the coming 1990-91 school year.

“We came together to support Calvin, and a lot of the campus came together to support his candidacy, and he won,” Fitzpatrick recalled. “This was the semester of unrest, but at the end of it, Calvin became [student body president] so that was making a statement right then and there.”

Butler won 79 percent of the students’ vote, according to the April 13 edition of The Scout. He wanted to focus on formulating an agenda for the incoming school year; the push for courses on race and multiculturalism now crossed over from the coalition to student government.

For Butler, it was a time for being shaped into an active leader–all on top of class schedules and homework. It was a catalyst for him to go to law school. Now, he’s an executive at the energy corporation Exelon. His time at Bradley opened up a greater purpose for him.

“I had a purpose in sitting back and saying ‘What can I do to serve others?’ and ‘How can I be a spokesperson for others who are not able?’” Butler said.

The period of transformation wasn’t limited to him.

Fitzpatrick expressed similar sentiments that the college days were an important time, especially for bringing people from different communities together to learn about one another. He said he applied the experience to jobs after college and still uses it frequently today working at State Farm.

“I deal with a cross-section of a lot of different people, and I got to understand where they’re coming from,” Fitzpatrick said.

Reflecting back on the semester, he said a lot of hard work went into conversations, reaching agreements on actions and dealing with the opposition.

“I remember not sleeping a lot of nights, not out of fear, but because we were doing so much, and I was getting one or two hours of sleep,” Fitzpatrick said. “For a whole month, I was operating on adrenaline.”

A Culmination of Protest

Heading toward the end of April, Fitzpatrick recalled that the campus was getting quieter. But on April 27, according to The Scout, students staged a protest of the university’s investments in South Africa.

Students protested by lying down and carrying signs in front of Swords Hall while the Board of Trustees took a vote on whether or not to divest their resources from the country; ultimately, they chose not to divest. It was not clear how much the university had invested in the country. In a statement, the board condemned the apartheid and said it encouraged corporations with holdings in South Africa to lobby for the opposition of discrimination and deprivation of human rights.

On top of this, Fitzpatrick said he began to hear rumblings about a potential appearance by the KKK in support of Matt Hale. Once he got the call on that Sunday that Klansmen had indeed appeared across the street from Harper and Burgess, the seriousness of the situation set in.

Butler was also unaware of the Klan’s presence on campus until he got a call.

“I would sit back and say it was eye-opening to think this was happening near our campus,” Butler said.

The Klansman clearly kept off-campus. The students mostly kept to themselves, though it’s reported in the May 4 edition of The Scout that a group of students claimed the Peoria Police held them back from confronting Klansmen; the police claimed the students were trying to be “inciteful.”

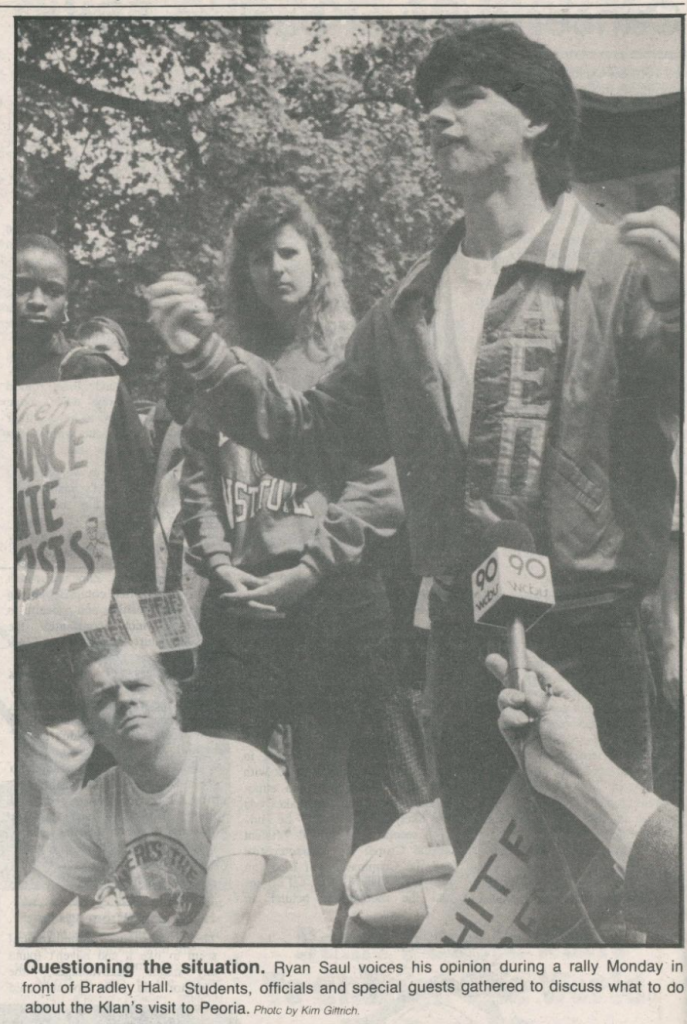

Students held a rally outside of Bradley Hall the next day protesting the Klan’s appearance and the Board of Trustee’s decision to not divest from South Africa.

As it was reported, students held an emergency meeting that night to decide what should be done in response to the Klansmen’s appearance. There was a call to cancel half of Monday’s classes to teach about racism, an emphasis of the original demands of the (newly-named) Multicultural Awareness Coalition to the administration and an investigation into any connections between Hale and the Klan’s appearance. Hale was quoted in The Scout that week saying he wasn’t aware the Klan was coming.

Considering this was The Scout’s last edition of the year, the record of details for the rest of the spring is only based on memory. Fitzpatrick recalled it became quiet again.

But once the 1990-91 school year began, The Scout reflected that the conversations over race were still taking place on campus. Events like the “Race Against Racism” 5K reminded students of the persistent issue at hand and of what happened in the spring of ‘90.

The presence of Hale also never left, as he continued to write letters to the editor, though then-Scout reporter Niels Sorrells recalled Hale turned his attention away from Bradley and more on the Peoria area after the spring.

The Times … They Are A Repeatin’

Once the ball was rolling for determined students to voice their concerns about racism on Bradley’s campus in 1990, it kept going.

“You didn’t slow down,” Butler said. “You didn’t ask why not or why. You did it because, if you didn’t, you were letting others down [and] you realized these issues weren’t going to get addressed.”

When Fitzpatrick reminisces on the coalition being formed in February of 1990, he said it was about bringing students together and putting thoughts and words into context and demands. He cited that moments like those happen every so often throughout history.

“Hearing that people are still talking about the Garrett Center still being the building that they don’t pay a lot of attention to, it doesn’t surprise me because that’s how society [acts],” Fitzpatrick said.

He was born a month after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, protested white supremacy on his college campus and now in 2020, as an adult, he is experiencing national unrest on race relations throughout the U.S. He said even when protests take place, those in power always try to quiet the backlash down. But he said those calls for change tend to be resilient.

“[The establishment will] neutralize it and get everything calm again,” Fitzpatrick said. “And just wait and then everything will just start simmering until something else erupts that causes it to explode again.”

Butler contextualized those events on Bradley’s campus in 1990 with those in 2020. He said moments come up that make it feel as though society has not made progress on adhering to those issues. He’s not surprised.

“We haven’t gotten to the point where we want just everyone to be successful and succeed regardless of the color of their skin, or their gender or their nationality, and we still find ways to divide ourselves,” Butler said. “That’s the part that’s frustrating and very disappointing.”