On Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor. The United States had stayed out of World War II up to that point, but the attack inevitably pulled America into the conflict.

As a hub for young men and women, Bradley became crucial to the war effort with military training, war aid efforts and skill-specific coursework. The Tech chronicled home front life on the Hilltop during that time.

“Like the rest of the country, Bradley students in general seem to be both outraged and bewildered by the sudden declaration of war which startled the world last Sunday afternoon,” stated The Tech in its first issue following Pearl Harbor.

A reader poll revealed that 77% of students favored war. It wouldn’t be long before students directly felt the impact: that same issue, the newspaper directed all male students 21 or older to complete a student report card on their Selective Service status.

By springtime, The Tech swapped some of its usual ads for cigarettes and Peoria businesses for those recruiting young men to the Army and Navy. Others encouraged students to buy U.S. defense savings bonds and stamps.

At the start of the 1942-43 school year, Bradley bustled with wartime activity. The Tech informed male students on how to enlist in the Army and Navy reserves. By Sept. 17, a total of 62 Bradley men had joined. That number jumped to 214 within two months.

Bradley hosted a special physical fitness class for enlisted men, inspired by the federal government’s request to help train students for future military service. Meanwhile, the women’s physical education curriculum added first aid training. Second semester, Bradley offered “war work” classes for female students which included “stenography, accounting, and other business courses, social work, science, mathematics, certain phases of engineering and other courses designed to train women to do their part in the war effort.”

Even faculty and staff got in on the act. Two librarians left campus to serve at naval base libraries in San Diego and Corpus Christi. Several male professors voluntarily joined the Armed Forces. And President Frederic R. Hamilton served on the federal Wartime Commission of Education.

In September 1943, Bradley’s Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) marched all over campus. The ASTP unit of 400 outnumbered the 340 civilian students, though ranks fluctuated based on war demands. The unit stayed for a school year, training but also getting a taste of college life with school dances, organized athletics and its own section in The Tech.

Outside of hands-on training, Bradley contributed to the war effort in other ways. The Tech reported frequent U.S.O. activities in Peoria, war bond and stamp drives, scrap metal and waste paper collections, and the establishment of a Red Cross chapter by women students. The newspaper also printed excerpts of letters from alumni and students in the service, a feature appropriately named “Khaki ‘n Blue.”

Following D-Day, veterans slowly began their return to the Hilltop. The number of enrolled vets doubled from fall 1944 to spring 1945 – which included one female veteran. Many joined the Horology department, others studying business or industrial arts. At Bradley and across the country, men took advantage of the GI Bill for college educations, while women who learned new skills on the home front pursued new majors, like engineering.

The war officially concluded on Sept. 2, 1945, around the start of the school year. Enrollment increased by a third, bringing an influx of students and activities. Campus organizations held social events. The men’s basketball team practiced for the first time in over two years. On Sept. 27, The Tech reported that 238 veterans had enrolled at Bradley, skyrocketing to more than 600 for the second semester. The university’s housing bureau scrambled to find extra rooms, converting the student center into a men’s dorm and allowing fraternity houses to increase their occupancies.

In December 1945, the school hosted a chapel service honoring the over 1,250 Bradley men and women who served in World War II. A reported 47 were killed in action. One of the returning veterans was Lt. Cmdr. David B. Owen, an alum who would become Bradley’s third president in early 1946. Owen had earned a special citation from the Navy for his work administering an extensive training and study program in the Pacific Theater.

Perhaps the war’s most lasting impact on Bradley didn’t actually happen during the war. In 1949, the university dedicated Robertson Memorial Fieldhouse, an arena converted from two decommissioned B-29 airplane hangars. Devoted basketball fans packed the legendary Fieldhouse to cheer on the Braves for decades.

Becoming Bradley University

Bradley Polytechnic Institute kept its original name for a half century, from the school’s dedication in 1897 to just after World War II ended.

Bradley’s mission had evolved in that time. “Practical” coursework offered by the Horological School and the School of Arts and Sciences were popular in the early years, but founder Lydia Moss Bradley, who passed away in 1908, specified in her will that the school should expand to include classical education, industrial arts and home economics. Over time, Bradley broadened its academic offerings. The institution became a four-year college in 1920 and continued to mature by the mid-century mark

In the first issue of the 1946–47 school year, The Tech reported that during the summer – specifically, on July 22, 1946 – the board of trustees voted to change the institution’s name to Bradley University.

The change was intended to reflect Bradley’s growth into a full university with five colleges and graduate offerings. At the time, the colleges were known as Bradley College (male students of liberal arts and sciences), Laura College (women students of liberal arts and sciences), Technical College (industrial arts and related vocational courses), Peoria Journal College (pre-professional programs and special two-year terminal courses with college credit) and the College of Fine Arts (art, music and drama schools). Special divisions included adult education, graduate study, summer study, and the landmark horology school.

“We regard our carefully worked out organization as a university as another step toward being of greater service to this region. The change of name and re-examination of our functions are part of the golden anniversary endeavor to fulfill Mrs. Bradley’s wish to have this institution serve the area in an increasingly effective manner,” stated President David B. Owen of the change.

The Scout is born

After five decades as The Bradley Tech, the student newspaper rebranded in 1946. Gone were the BPI days, making The Tech nickname outdated. In fall 1946, the student newspaper held a renaming contest to find a moniker fitting of Bradley’s next chapter.

On Dec. 5, the student newspaper became The Scout, a name chosen out of more than 70 submissions by a committee of students, faculty and alumni. The name tied into the Native American theme used for the university’s mascot and for several campus spaces, like the Wigwam and Teepee.

“As the Indian scouts reconnoitered new fields for their tribes, so ‘The Scout’ will continue the work of ‘The Tech’ in ‘reconnoitering’ the field of news for the campus tribe,” stated the newspaper.

The Native American theme was especially prevalent in the renaming contest – the second- and third-place choices were The Totem and Tom-Tom, respectively. In fact, the newspaper had been using Native American themes and imagery years before the official renaming. The submissions were likely influenced by Bradley’s athletic teams, which were renamed the “Braves” in the 1930s after going by the “Indians” in the early decades.

(Note: Native American imagery in collegiate sports and culture was common in the 20th century. Bradley phased out Native American imagery in the early 1990s.)

The Scout has graced the newspaper’s masthead for 76 years and counting.

Basketball triumphs in the 1950s

When the Bradley men’s basketball team first took the court in 1902, things looked a lot different. The game’s rules, pace and style of play were rudimentary and slow. The Bradley squad had only five players and two substitutes and played just seven games that season, with results that looked more like baseball or football boxscores (the first game: Bradley, 12; Invincibles, 8). In fact, football was the most popular sport on campus – a team no longer in existence!

The tide started to turn in basketball’s favor in the 1920s, when legendary multi-sport coach A.J. Robertson took the helm. “With King Football beheaded, basketball now occupies the throne of athletics at Bradley,” explained The Tech on November 24, 1920, impressed with the group of 30 students trying out for Robertson’s five-man squad.

Robertson coached the basketball team from 1920 to 1948, becoming the winningest coach in school history with 316 victories. He guided the team to its first three NIT Tournament appearances in 1938, 1939 and 1947. And he was instrumental in helping Bradley join the Missouri Valley Conference. At the time of his passing in 1948, Robertson’s legacy loomed large over the Bradley Braves basketball program.

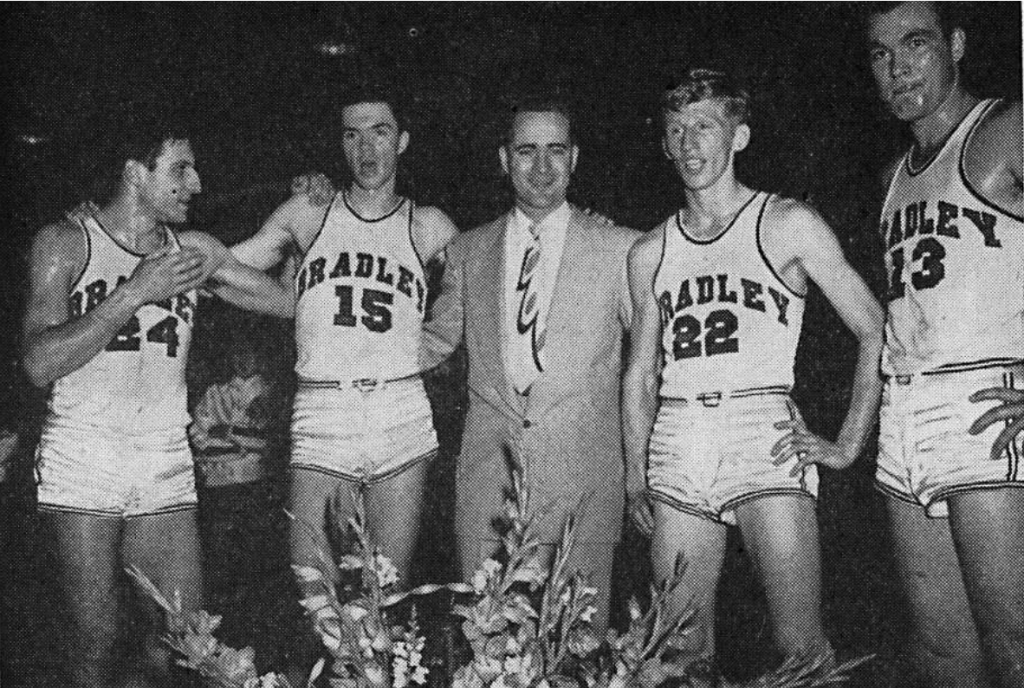

The foundation laid by Robertson helped Bradley become a national powerhouse in the early 1950s. Led by new coach Forddy Anderson and star players Paul Unruh and Bob Carney, the Braves appeared in two NCAA Tournament championship games in five years, Bradley’s only two title games to date.

In the 1950 tournament, Bradley defeated UCLA and Baylor in the Western regionals to advance to the championship game. The Braves faced City College of New York (CCNY) at Madison Square Garden for the main event. To support the basketball stars (and keep them informed on Hilltop happenings), The Scout made a special delivery of 1,000 newspapers to the team’s New York hotel for players and boosters alike.

The Braves battled hard for the title, but narrowly fell 71-68 to CCNY. Still, the university, the city and The Scout showered praise on the team’s tourney triumphs. The newspaper published a photograph of hundreds of happy fans swarming a Trans World airplane bringing the Braves home. There were more pictures of a celebratory parade in downtown Peoria with players riding in open-top convertibles.

Unfortunately, Bradley’s first NCAA championship game appearance would be stained with scandal. In 1951, CCNY was implicated in a point-shaving scheme where the team played to a specific point margin determined by gamblers. The game-fixing investigation eventually expanded to 32 players and seven schools, including Bradley, alleging the players fixed dozens of games from 1947 to 1950.

In July 1951, five Braves admitted to taking bribes for games against St. Joseph’s and Oregon State. Three were indicted by the New York District Attorney and later received suspended sentences. That included Braves star Gene Melchiorre, who was the first overall pick of the 1951 NBA Draft but quickly banned from the NBA for his role in the scandal.

“The eyes and ears of the entire sports world will be following the Bradley university (sic) Braves as they take to the hardwoods next season to reestablish their once splendid reputation. As the popular coach Forddy Anderson put it, ‘it’s a thing of the past’ – but a past that has not been forgotten nor will be forgotten for years to come,” stated The Scout ahead of the 1951–1952 season.

Despite the misconduct, the Braves didn’t stop competing. In 1954, Bradley made another deep run in the NCAA Tournament. The Scout detailed all games in the Western regional, where Bradley knocked off Oklahoma City, Colorado and Oklahoma A&M to advance to the Final Four in Kansas City.

There, the Braves defeated USC in the semifinal. The title game against La Salle and future Hall of Famer Tom Gola proved more challenging as the Braves lost 92-76, finishing runners-up once again.

After the second national championship appearance, Bradley made the NCAA Tournament seven more times: 1955, 1980, 1986, 1988, 1996, 2006 and, most recently, 2019. Luckily for Braves fans, The Scout has chronicled Bradley basketball for over a century and will continue to do so as the 2023 MVC regular-season champs prepare for another run.

Victoria Berkow served as editor-in-chief of The Scout from 2013–2014. After graduating from Bradley, she earned a master’s degree in history from the University of Georgia, specializing in sports history. Berkow works as a historian for an archival services company today.