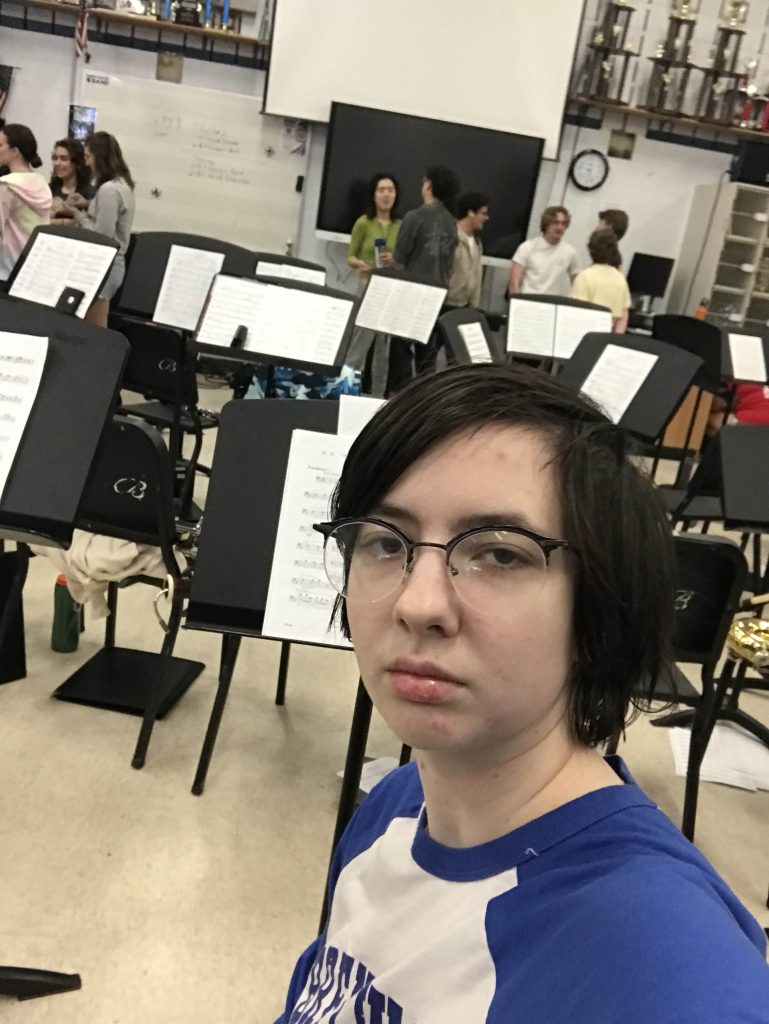

My feet ache from marching all day, and it’s unbearably hot. All the other kids around me reek of sweat, and I’m sure I smell the same. I stand in silence, gripping my trombone with all the strength I can muster in some futile effort to drown out the chatter and laughter of my peers. Still, through all the noise, I hear my name through the crowd.

“Cassie is one of the worst trombonists we have.”

I don’t even bother to look for who said it. After all, I know it’s true. Getting air through the horn is a challenge, let alone making decent-sounding music. It doesn’t stop the tears from welling up in my eyes. Still, I remain standing.

This was my freshman year of high school when I decided joining the school marching band would be a good idea. Newsflash: I wasn’t particularly good at it, and my peers made sure I knew it.

The music was fast, high-pitched and like nothing I’d ever experienced before. Even if I could hit the difficult notes, I physically wasn’t capable of playing some parts of it, my arms not capable of reaching as far as necessary quickly enough. My body wasn’t used to the lung capacity I needed or the long exposure to heat. My legs felt like they were barely working at the end of the day.

All around me, I could see people who looked at me with contempt for all of my failings. Some people just told me I was horrible; others were more subtle. It’s like they thought if they criticized me enough, to my face or behind my back, I’d finally realize what was wrong with me and step up, but I was already trying so hard. I knew half of the people there never had to try half as hard as I did just to earn basic respect, and even then, it was never good enough.

Yet, I kept pushing forward.

I worked with the school’s trombone teacher. I started practicing during my free study hall periods. People who walked by sometimes complimented my playing, and the band teacher applauded my dedication.

The next year was the pandemic. Because we had to social distance, I was the one who had to train the new freshmen trombonists instead of the seniors. One of them grew attached to me and encouraged the other kids to vote for me for the band’s Most Improved Sophomore award. I still have it on my shelf.

In my junior year, thanks to hours of practice, I got into the highest level of concert band. Despite this, in marching band, I was still given sheet music for the people in lower bands. In practice circles, I was forced to stand with the sophomores, people who had completely different parts than me, while my fellow juniors stood in the front.

Life got worse. Teachers were stacking homework like it was Tetris, and all the horrible events from the year prior, like finding out my childhood friend turned out to be lying about everything, my cat going missing and being presumed dead and my grandfather dying, were all toppling down around me.

Still, I kept pushing forward.

But then I started having breakdowns during marching band. My peers accused me of overreacting, not understanding that I had no control over how I shook and hyperventilated.

It became normal for me to constantly be working on either homework or the trombone at school and do nothing but lay in bed at home. It became normal for indentations of my teeth to be on my wrists.

It’s the last day of marching band, and I stop pushing forward. Instead, I ditch band class for the first time. I don’t intend to come back. I leave school and walk to the entrance of the interstate and just stand there, watching as fast cars pass me by. It takes me fifteen minutes to step away and begin my venture back.

I decide to quit marching band.

People who surrounded me in the horrible heat stroke-inducing weather all those years told me they were sad to see me go. Some even tried talking me out of it, bargaining to try to keep me in.

They gave me all the encouragement and promises I would’ve dreamed of hearing an ounce of earlier instead of the constant criticism and refusals to help the hundreds of times I’d asked, but I stuck to my guns.

Senior year, I was the only student in band class not in the school’s marching band. My farmer’s tan was fading, and my legs no longer constantly ached. However, this relief was nothing in contrast to the knowledge that I did not need to be constantly pushing forward. Instead, for the first time in years, I could just be.

I’m now in my sophomore year of college, and I’m pushing forward once more, but with mental health accommodations and new knowledge. I don’t need to be perfect to deserve love, and people don’t have to understand me for me to be who I am.