Down four on the road in overtime, freshman guard Montana Wheeler could sense Bradley needed a bucket.

The Braves had missed four of their first five shots in the extra period, still reeling from a full-court buzzer beater as time expired. Their momentum was gone, and the Sycamore crowd was alive.

Wheeler stood at the top of the key, scanning the defense as the shot clock ticked towards zero.

With five seconds, he began his pursuit to the rim, faking right, then quickly crossing back left, spinning towards the middle of the floor and finishing over a Sycamore defender.

He’d done his job, giving a stale offense the spark it needed to recover from the shock at the end of regulation.

A few minutes later, Bradley would call on him again.

With 27 seconds to play, the Braves trailed 91-89. Wheeler caught the ball and, as he began to use a ball screen, head coach Brian Wardle yelled at him to shoot.

He listened.

The three-pointer snapped through the net to give Bradley a one-point lead.

“When the coach tells you to shoot it, you shoot it,” Wheeler said. “That’s the ultimate confidence, the ultimate green light. I let it go, and I made it.”

The Braves won the game 108-99, their fifth straight victory, but perhaps more importantly, Wheeler had delivered in the biggest moment of his young career.

In crunch time, he was poised. Nothing phased him.

Not the suffocating pressure of a jeering crowd or the anxiety of a winding shot-clock.

It seemed like he was built for games like this.

And that’s because he was.

Basketball in his blood

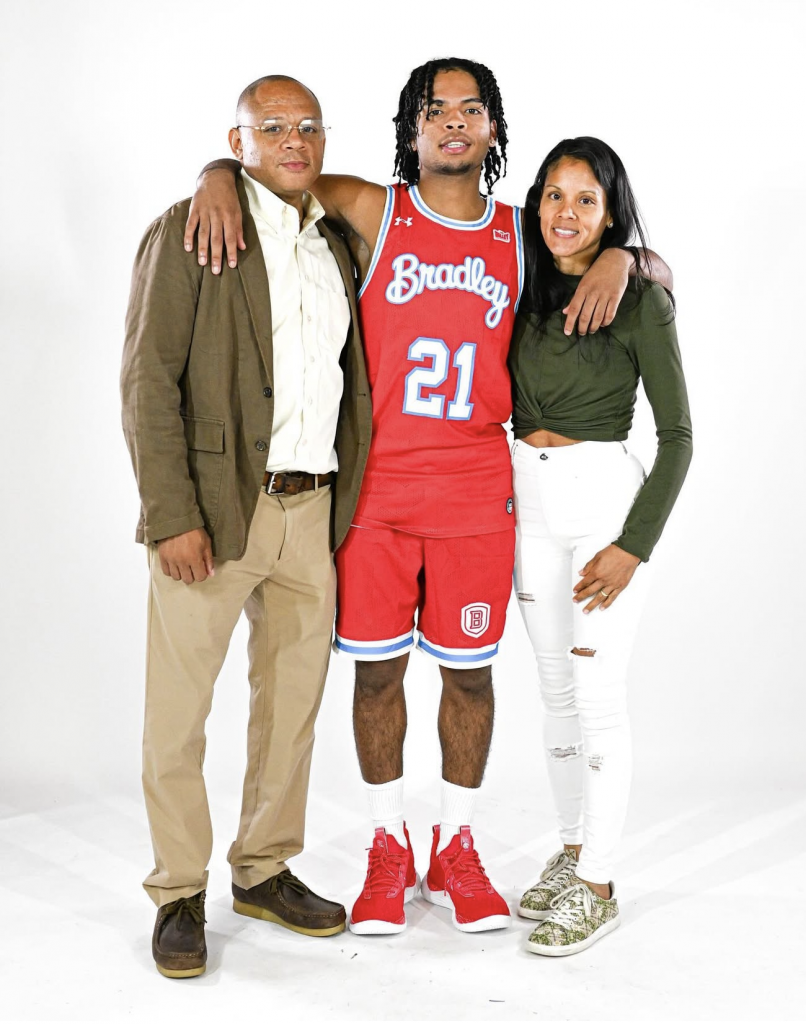

Wheeler grew up in Houston, Texas, with basketball in his blood. His father, Teddy Wheeler, has decades of experience coaching basketball and has helped over 60 players secure Division I commitments, including Wheeler’s brother Savhir, who was a top 80 recruit according to ESPN and played college basketball at Georgia, Kentucky and Washington, averaging 14 points and nearly eight assists during his collegiate career.

Naturally, Wheeler grew up close to basketball. He’d sit and watch his father coach and his brother compete against future NBA players, including Philadelphia 76ers guard Quentin Grimes and Golden State Warriors guard LJ Cryer. It was in these highly competitive atmospheres that his relationship with basketball began.

“Montana was always super competitive,” Savhir said. “I think that just came from being around me when I was in the gym. The dudes I was playing against or working out with were always older than me, so he always had a competitive edge, because he was always trying to prove that he was as good or he could fit in, or that he could play with us, even though he was much younger. And with that, he not only had a competitive spirit but was also a joy to be around.”

By the time Montana reached middle school, his older brother was one of the highest-ranked recruits in the nation and was taking trips around the country to a few of the nation’s most storied programs, with Montana tagging along.

As he watched his success at the collegiate level – making all-SEC teams and the Wooden Award Watch List – Wheeler began to take the game more seriously around eighth grade.

He had a blueprint.

“Savhir was a major influence on me,” Montana said. “It was crazy seeing my brother, whom I grew up with, play at Kentucky versus North Carolina, playing versus Duke at Madison Square Garden. That’s something I’ll never forget, and it inspired me to play basketball because I knew my brother could do it.”

“He gave me hope.”

Once Montana began taking the game seriously, he quickly became one of the best players in Texas, even playing a few games with his dad’s 17-and-under AAU team on a national circuit.

“I didn’t coach him at first,” Teddy told the Scout. “I tried to put him around other really good coaches that I trusted. So during that eighth-grade year, he went to MADE hoops with my childhood best friend, who runs an AAU program in New York called the New York Lightning. And then, he would spot in some games every now and then on my 17-and-under team in the eighth grade.”

In games against players 3-4 years his senior, Wheeler held his own, and schools began to take notice.

By the time he enrolled as a freshman at Houston Christian High School, where his dad was the coach, he’d already accumulated offers from Texas Tech, St. John’s, Texas A&M, Louisiana State University and Lamar University.

In his sophomore year, the Wheels really began to turn. He went from averaging 13 points and four assists to 22 points and six assists and helped the Mustangs improve to 31-4. Wheeler led Houston Christian to a Southwest Preparatory Conference Championship and was named the Texas Private School Player of the Year by the Texas Association of Basketball Coaches.

As his high school career went on, he kept improving, and the offers kept coming. Twenty-four points and eight assists as a junior earned offers from Rice University, Kansas State, Old Dominion and the University of Central Florida.

Wheeler and the Mustangs were on track for a consecutive state championship when disaster struck.

He broke his hand.

Blessing in disguise

While nursing his injury, Wheeler was temporarily without basketball for the first time in his life. During his time away from the court while he sought second opinions from doctors, the guard found a newfound love: the theater.

“It made me realize that there are other things besides just being a basketball player,” he remarked about the injury. “I started to take the theater a little bit more seriously, just like going to the extra practices and stuff.”

Though Wheeler was away from basketball, he was still becoming a better player off the court.

“It’s prepared for the bright lights,” Wheeler said. “In theater, everyone is just watching you, and you have to perform to the best of your abilities, just as in basketball, when we’re playing in front of these big crowds. You’ve got to be at your best. And that’s something theater taught me: just be at your best at all times.”

Wheeler thrived in theater, just as he did in basketball, notably playing a prisoner in Xavier’s rendition of the musical Guys and Dolls.

He wasn’t Troy Bolton, but being in a supporting role helped Wheeler become a better teammate.

“I think it taught him that he didn’t have to be the star,” his father said. “That he could enjoy being a part of something bigger than himself. He was such a tremendously skilled young player. He had all his success early on. The theater piece helped him recognize that everybody’s contribution is important.”

“It helped him appreciate the guy who’s just setting the screen,” Teddy continued. “It helped him appreciate the guy who just has to take the ball out, because in theater, the person who’s singing was the lead, they’re getting all the cheers. But it’s such a big production, so it teaches you to appreciate and show gratitude to the people whose names are in the credits, even if they’re not the first ones called.”

Eventually, Teddy and Montana found a doctor who cleared him to return to the court with a low risk of re-injury. Wheeler was still in pain, but he played through it.

“It showed a level of courage, commitment and loyalty,” Terry said about Montana’s decision to play through the injury. “The second doctor we saw was a hand specialist at UT, who told us that it was a low chance at re-injuring the hand, but if he did, he’d have to get surgery and miss his final summer of AAU. But he poured so much into winning back-to-back state championships that he put it all on the line. So I was tremendously proud of him.”

With Wheeler not at full strength, the Mustangs lost 70-53 in the state tournament, but he’d proved how far he was willing to go to win.

Feats of bravery like these put him on head coach Brian Wardle’s radar.

Betting on the Braves

“Montana had production against high-level talent,” Wardle recalled about his interest in the freshman guard. “No matter the size that he played against, he always produced. He was a fiery competitor. I fell in love with him because I was scouting another point guard who’s closer to here. He completely destroyed that point guard, and that’s when I jumped all over him and said, ‘I want this guy,’ just because of his competitive spirit and how hard he played and how he competed.”

Bradley offered Wheeler during his final AAU season, and he committed in September 2024, choosing Bradley over several other high-major options – a decision based on transparency and the opportunity to compete.

“It wasn’t really about the conference, or the school or the name on the front of the jersey,” Wheeler said. “It was about the fit to me, and I feel like Coach Wardle and his staff offered me a fit that would help me improve my game. I also wanted the opportunity to compete and play from day one.”

Wheeler spent his senior season at Xavier Academy after his dad took the head coaching job, avenging the previous year’s state playoff loss and finishing with a second state championship in his final season.

But before he could step on campus, another obstacle presented itself. During the offseason, Wardle was forced to rebuild his coaching staff after many of his assistants were promoted or received opportunities elsewhere.

This was difficult for Terry, as he’d always either coached Wheeler himself or placed him in the hands of coaches he trusted.

“That was disappointing, because I was looking forward to seeing those guys interact with my son,” Terry told the Scout. “But the head coach is still the head coach. Yes, we missed opportunities to work with some assistant coaches, such as Coach [Jimmie] Foster, but I’m still grateful that Wardle is his coach. Yes, I’m not there, and he’s not at home, but he’s being coached by one of the best coaches in the country.”

To this point, the gamble has paid off.

Wheeler hit the ground running as soon as summer workouts began, establishing himself as a player who could impact winning early on.

“He’s been very consistent since he arrived here,” Wardle said. “He set the tone in the summer and fall of who he was going to be with how hard he played; his teams won a lot. I love it when we were always in practice or doing workouts in the summer and fall, and his teams would win. He still has some freshman mistakes here and there, but he’s as ready to play as a freshman as I’ve had in a while, probably since Connor Hickman.”

When the season started, Wheeler made a quick first impression, scoring six points and four assists in his debut, nine points and four assists in a road game vs. San Francisco and exploding for 16 points and six assists in Bradley’s win over Princeton.

Throughout the season, Wheeler has made plays in moments usually unbecoming of a freshman. He’s earned the trust of head coach Brian Wardle and his teammates, and their praise has followed whenever his name comes up.

“I think he could be one of the best mid-major point guards in the country,” Jackson Seastrunk, Wheeler’s former high school and current Bradley teammate, said. “Even though we already have one of the best on the team, I think by the end of this season we’ll have two. Over his college career, I think he’ll be one of the best point guards in the country.”

Whether Wheeler ultimately reaches the ceiling his coaches and peers envision remains to be seen. But given his work ethic, competitiveness and feel for the game, it would be brave to rule out that possibility.

After all, basketball has always been more than just a game to him – it’s in his blood.