How does an institution develop a 125-year legacy?

It’s taken thousands of dedicated students over that time to nourish, grow and evolve Bradley’s student news publication.

Mere months after Bradley Polytechnic Institute began offering its first classes in the fall of 1897, conversations began about establishing a student news magazine and a goal was set to launch it early the following year.

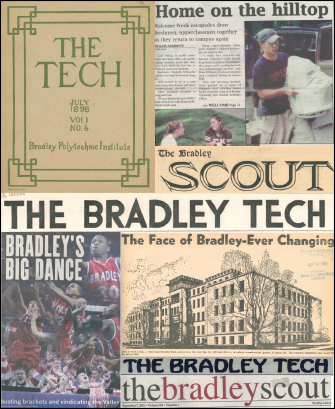

So it was that the Bradley Tech debuted in February 1898 at a comparatively modest 7 inches by 10 inches to a page and an ambitious goal to publish once monthly. (Some years it didn’t quite work so well, with the 1898-99 staff only publishing thrice.)

Opening Benediction

Here’s how editors of the first Tech explained their goals, as written by Editor-in-Chief Lucie B. Clark:

“We appeal to the student body to aid us in this attempt,

And may it never regret the support to the Tech given,

We ask no more; only the just tribute

That all must pay in fealty to enterprise.

Help the Tech, maintain the standard we hope to set,

And it shall become a power that must compel your pride;

Help us to rouse the flagging interest in athletic sports,

And strengthen our allegiance to our Alma Mater;

Help us to revive the drooping flower of College Loyalty,

That flower that should be brightest in the wreath of college life;

And may the Tech through long coming years,

Complete the cycle of another century,

And live but to promote good fellowship and truth.”

A different time

The Tech accepted subscribers – provided they paid in advance. Rates ran 10 cents for a single copy, or a discounted rate of 50 cents for a six-month subscription.

Not everyone paid, of course, By 1908, editors were using a filler ad to disguise a short column. It read: “This is not an attempt to fill up space. It is an attempt to get our subscribers to pay their long overdue subscriptions.”

Today its successor, The Scout, is available for free to students, employees, alumni and the community online – and, indeed, was free to all students in print format for years. Formal “subscriptions” ended earlier this century when it became cost-prohibitive to mail individual copies.

Editors acknowledged the values of the time in their opening editorial, noting the gendered expectations of the era: “Boys” liked athletics, while some few “girls” might deign to watch; the ladies knew how to sew, but the gentlemen only displayed an interest if their trousers tore or a button popped.

The Tech, though, was no place for stereotypes based on gender.

“It has been found that a school paper is the one thing in which boys and girls can take an equal interest and part, for in it all may express their opinions,” they wrote.

So it is today for all comers.

While today readers expect to find clearly delineated news, opinion, entertainment and sports coverage, the early era regularly featured short stories, poems, gossip and more.

Student support needed

One final truism from those early years has remained with the publication through all its permutations, from monthly editions to the electronic frontier:

“This is your paper, students of the Polytechnic, and it is dependent upon you for its support and welfare, therefore we ask you to help as much as possible. We urge each and every one of you who take pride in your school to assist us by contributions, for in this way only can the Tech be made a success.

Loss of a founder

The January 1908 edition of the Tech carried a short bulletin advising readers of founder Lydia Moss Bradley’s illness, though it remained hopeful for the 91-year-old’s health.

Her death before the February edition occasioned deep mourning, with memories solicited from Bradley Polytechnic’s then-director, Theodore C. Burgess and his predecessor, Edward O. Sisson.

At Bradley’s funeral, the Tech reported, “a blanket of red and white carnations, the gift of Bradley students, was left upon the coffin even as it was being lowered into the grave, thus symbolizing the intimate connection ever existing between the Institute and its Founder.

The Tech staff, led by Editor-in-Chief George Mahle, memorialized the Peoria legend, who still lived just blocks from campus. While paying her tribute, editors noted that “we realize, however, that there is only one way in which we can show our love for our founder, and that is to conduct ourselves in such a manner that ‘Bradley’ will always be synonymous for integrity and nobility and honor.”

What’s football without fans?

Whether polytechnic or university, Bradley has occasionally battled malaise among its fans. When football was still the marquee sport in 1914, editors had to chide members of the student body to show their support.

“A college without enthusiasm is no college. Enthusiasm is what makes school life full of pleasures for the present and full of memories and inspiration for the future. If the students of Bradley fail to develop a whopping big amount of school spirit this Fall, they deserve to have their tuition returned, for the year won’t mean much to them without it.”

World War I

The outbreak of World War I brought a sanguine response from editors, who noted days after the war’s outbreak that it was still not known how many men attending school would be subject to the draft.

However, they wrote, “it is heartening to know that those who are called will be in some measure prepared in the rudiments of drill work. … The few weeks’ training that our boys will get, as well as the boys of a great many other colleges in the country, will go far toward hardening them to the rigorous training they will receive in the intensive training camps which will be established throughout the country.”

Bradley was the site of “Camp Bradley” drill- and training-ground, with space given over to lodging and drilling. Because of that work done by contract with the War Department, editors temporarily suspended publishing the Tech. Editors explained the hiatus when they returned to publication:

“Owing to the army situation at Bradley it was unable to attempt the usual publication in the fall. All the school was disorganized by the government control and the attempt would have been foolish. Nevertheless the school paper was greatly missed and immediately after demobilization plans were started toward organizing the Tech,” that partial year’s editor in chief, Leslie Gage, wrote in January 1919.

Larger print editions, growing college enthusiasm

By 1921 the magazine style for the Tech was gone, replaced by a broadsheet newspaper that mixed campus news, club activities and athletics on the front page. It boasted that running at least eight full broadsheet pages, it was “the largest weekly publication in the state of Illinois and on par with any college weekly publication in the United States.”

Within a couple years, the paper had on its front page the exciting news that college officials were aiming to see 35,000 fans attend home football games by the end of the season, a significant rise over the 21,000 who’d seen “the 1922 champion eleven in action on the Bradley field.” The team ended the prior year 9-0-1 and would go 6-2 in 1923.

Weeks later as the season got well under way, the Tech published a series of cheers for athletic games so everyone could join in. One ran:

“Fight on Bradley.

’Tis our fighting tune.

Touch down Bradley

For the old maroon.

Former glories we recall,

Come on fellows—

Come on fellows—

KICK THAT BALL!

Let’s go Bradley

All the way to fame.

Plunge on Bradley.

Pluck will win the game.

B-R-A-D-L-E-Y

Never Fear!

But Cheer!

For dear old B. P. I.”

Not-so-Roaring 20s

The 20s might best be remembered for its loosening morals – speakeasys, flappers, higher hemlines and wilder dances – but Bradley wasn’t entirely cutting loose.

In 1929, women at the school were told their participation in the annual “B” club pajama parade was forbidden, though they were welcome to watch “the men go through their antics.”

Regular advertisers for the publication sold clothing, hats and other accessories to men and women alike. One regular advertiser for such wares was P.A. Bergner Co., the downtown Peoria department store that would later grow into a multi-state conglomerate before its 2018 bankruptcy and later rebirth as a digital-only retailer.

Another advertiser tried to pull students in for cafe lunches by boasting their second cup of coffee was always free.

Upbeat in facing Great Depression

In early 1932 the Great Depression was raging around the country. While the Peoria region was affected, it remained more insulated than other cities, students were told by a Tech reporter in the annual edition focusing on business studies at Bradley.

Association of Commerce secretary O.F. Lyman told the Tech that overall the city was doing better than similar communities “over the 100,000 population mark.”

That was, in part, because of the city’s “advantageous locality” – a similar argument to today, with Peoria’s proximity to river, road, rail (and now air) transportation.

Chris Kaergard, 2003-04 Scout editor and current adviser, spent 17 years as a newspaper reporter and editor. He now serves as historian at The Dirksen Congressional Center in Pekin.