Every day, people are affected by opioid addiction and overdoses. But what if these afflictions can be prevented?

Bradley professor Mohammad Imtiaz, alongside two other researchers, Charles Bandoian and Thomas Santoro, are in the final stretch of their development of a device that recognizes the signs of an overdose. Imtiaz serves as the chief engineering officer of the team, Bandoian serves as CEO and Santoro as the chief medical officer.

However, before anyone can understand the device itself and why it will be so important, it is necessary to understand how overdoses occur and the impact that opioid addiction has on everyday people.

“When we talk about an opioid overdose, our office will see fentanyl … [and] generally, the fentanyl that we see is mixed with heroin,” Jamie Harwood, Peoria County coroner, said.

According to Imtiaz and Bandoian, the start of the development began with a search for hope. Both understood the severity of opioid use and how overdoses can affect not only a person but a person’s family.

Bandoian further clarified that the device will mainly be made for people who want to get off of drugs.

“You have to be monitored [and] working with a physician or a nurse practitioner to help get you off of this, and there are ways that this can happen, but [the device] is a lifeline,” Bandoian said.

The device that the team is developing has been in the works for quite some time. The idea was first proposed by Bandoian and Santoro. They had a small team of students working on the project and met Imtiaz when they brought the idea to Bradley.

Upon meeting Imtiaz, Bandoian said that it was necessary to have him on board for their team.

“A project like this does not need one expertise; it needs multiple [areas of] expertise,” Imtiaz said. “It needs people from the medical side, doctors, it needs engineers, it needs people who know mechanical engineering, it needs people from the business side to understand whether this is useful or not.”

As the developmental process went on, the team had to think about the signs of an overdose and how to prevent the deaths caused by them, especially for those who might not have resources or those who have been incarcerated.

“Those who might go into incarceration … they’re not given any treatment,” Harwood said. “So, when they leave, their tolerance is a lot lower than what they anticipate and they don’t understand that. And then they overdose on the opioid or the fentanyl or whatever it is … and it takes their life because they just don’t have the resources that they had before.”

The process of the research was not always easy. The team went through multiple struggles with the design, such as figuring out the correct size to fit on someone’s arm or leg and trying to figure out how to keep the needle injection clean.

“If a needle is embedded in somebody for four hours a day, that’s going to get infected, so this doesn’t work,” Imtiaz said. “You want a device that’s not bulky. All of those issues are critical issues [and] engineering challenges.”

How the device works sounds complicated but is in fact quite simple. Imtiaz explains that the device must be able to sense an overdose, which it is able to do through a microcontroller with an algorithm that will constantly monitor the oxygen saturation levels of the wearer.

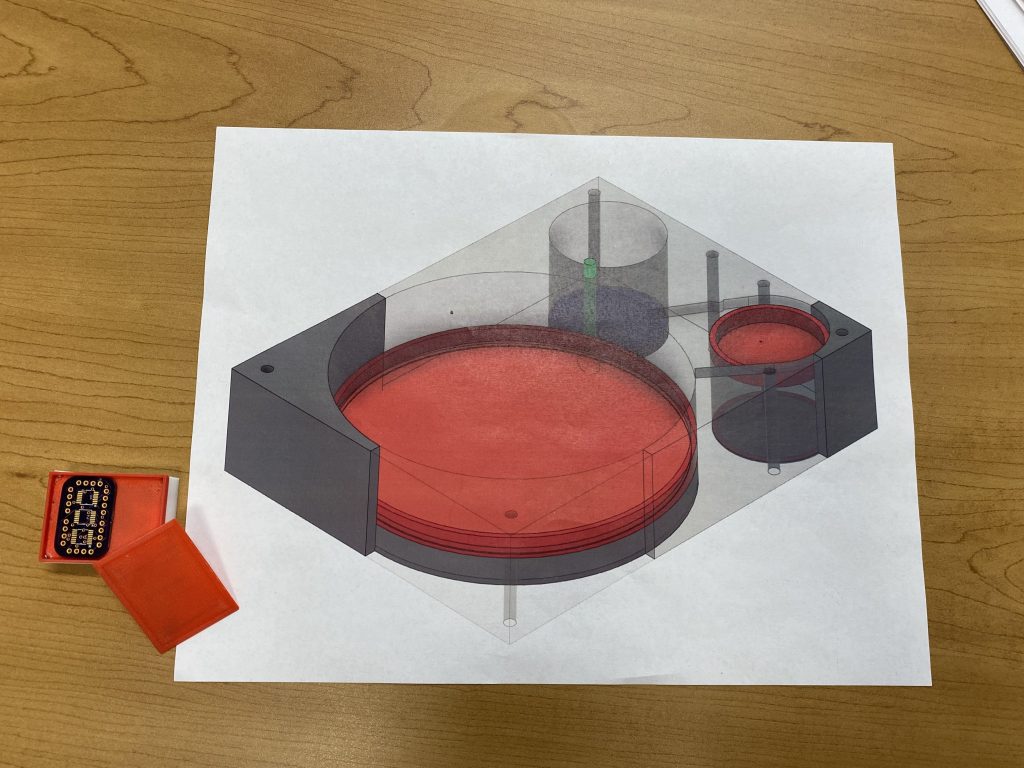

There is also a needle inside of the device, held in a sterile environment inside of a compartment.

The chamber located at the top of the device holds the antidote, a drug called nalmefene which will try and slow down the process of the overdose until medical attention can arrive. Below it are sensors with a microcontroller on top of them. Once an overdose is detected in the wearer, compressed gas is released in the chamber, which then pushes the needle into the skin with the antidote.

Then, as the antidote is injected, the electronics in the device begin to call 911 and send out the GPS location of the person overdosing to the police. If the wearer is not coming out of the overdose, the device is also equipped to give another injection.

The device itself is to be worn on a fresh piece of skin, whether that be on the arm or the leg. This is so that when the needle injects, it goes into a place where the antidote can spread around.

As Bandoian shared, the device is not only made for opioid overdoses. It can also be used for those with any other underlying health issues, which he found to have a personal application for him.

“I’m going to get one of these for my dad,” Bandoian said. “He’s not an opioid user, but this will monitor his heart and his breathing, and if he has a problem and has something … go wrong, it will call 911. It will send the coordinates as well as his vitals and then start calling his contact list.”

The team has high hopes for their device and has plans to release prototypes to the public very soon, possibly by the end of this year. They go more in-depth on the process in a paper that they published in 2021.

Regardless, they won’t be done working until the opioid overdose crisis ends.

“Even if you can save one life, your whole work has been awarded, but imagine saving thousands of lives,” Imtiaz said.